Originally published July 19, 2019 and updated with new work and new podcast in October 2023.

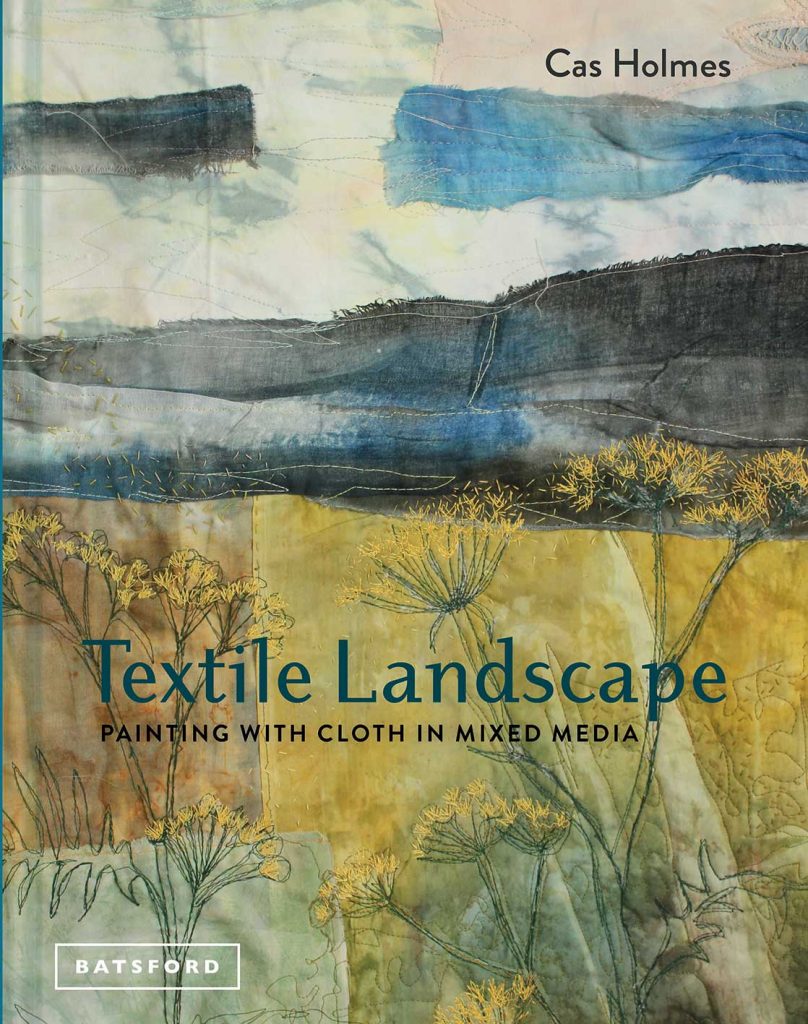

As one of the UK’s most popular mixed media artists, Cas Holmes needs no introduction. Her accomplishments include the publication of several books, work in public and private collections and countless international exhibits.

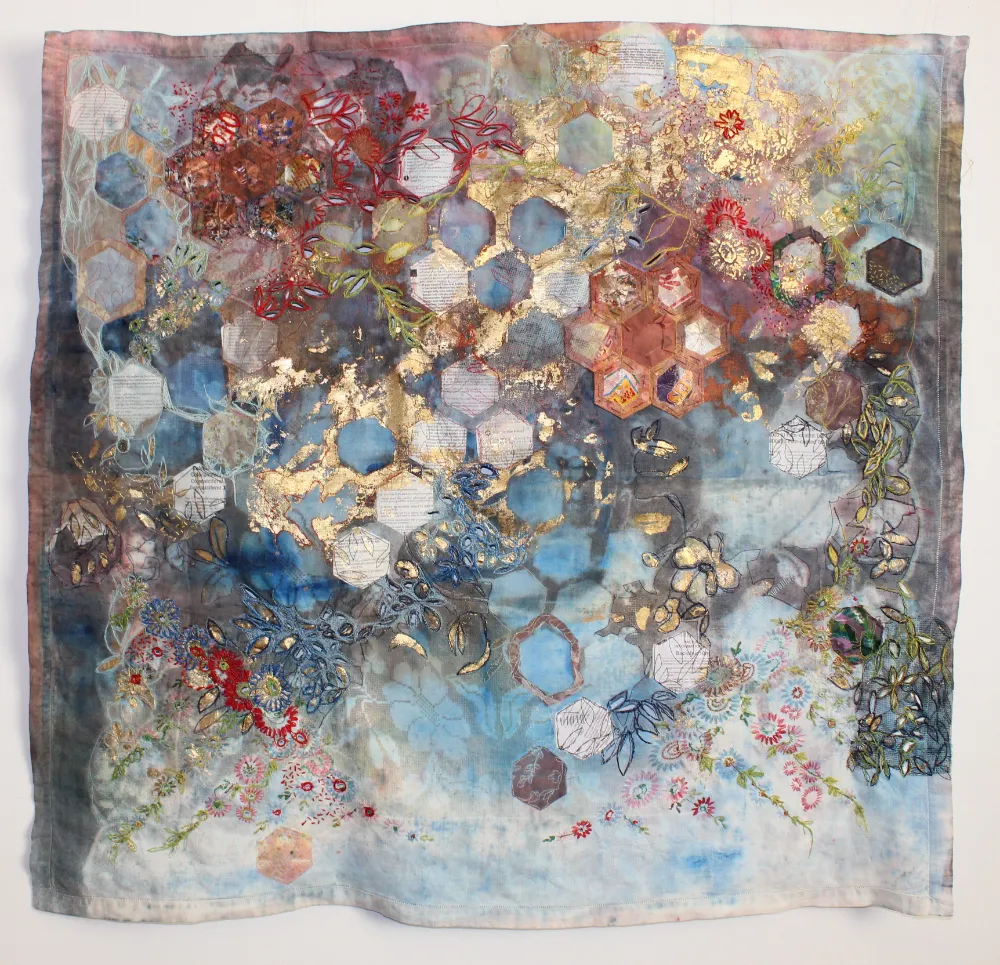

Cas’ work embodies her desire for travel and collecting materials which are then stitched into her work: A signature synonymous with her style, which has been described as painting with cloth. An icon of the textile art world, we caught up with Cas on our latest episode of Textile Talk to discuss her work, inspirations and current projects.

Textile Talk with Cas Holmes

Listen to the podcast now or read through the transcript below.

Cas Holmes

Joining me for this episode is Cas Holmes, who is a British artist, author and tutor of Romani heritage, specialising in textile work with found materials.

She trained in fine art and is interested in interdisciplinary projects in community and gallery settings to demonstrate the accessibility of mixed media textile processes. Her practice centres on the use of sustainable materials and themes surrounding issues of identity and place. She has researched in traditional paper and textile crafts in Japan and India, which continue to inform her practice and writing. And that was through a Winston Churchill Fellowship, Japan Foundation Fellowship and Arts Council England Professional Development Award.

She collaborates with organisations and projects on curatorial and community events, including the Romany Cultural and Arts Company, as a recipient of Gypsy Maker Award, and with Craft Scotland on a collaborative exhibition called Places Spaces Traces, which is an exploration of the concept of place and our understanding of the importance of heritage, how our inherited traditions, monuments, objects and culture can impact upon our identities and the space we call home. This touring exhibition was launched on Light vessel 21 in Graves End and with Anna Three in Antwerp. Cas’s work and projects are reflected in her publications for Batsford.

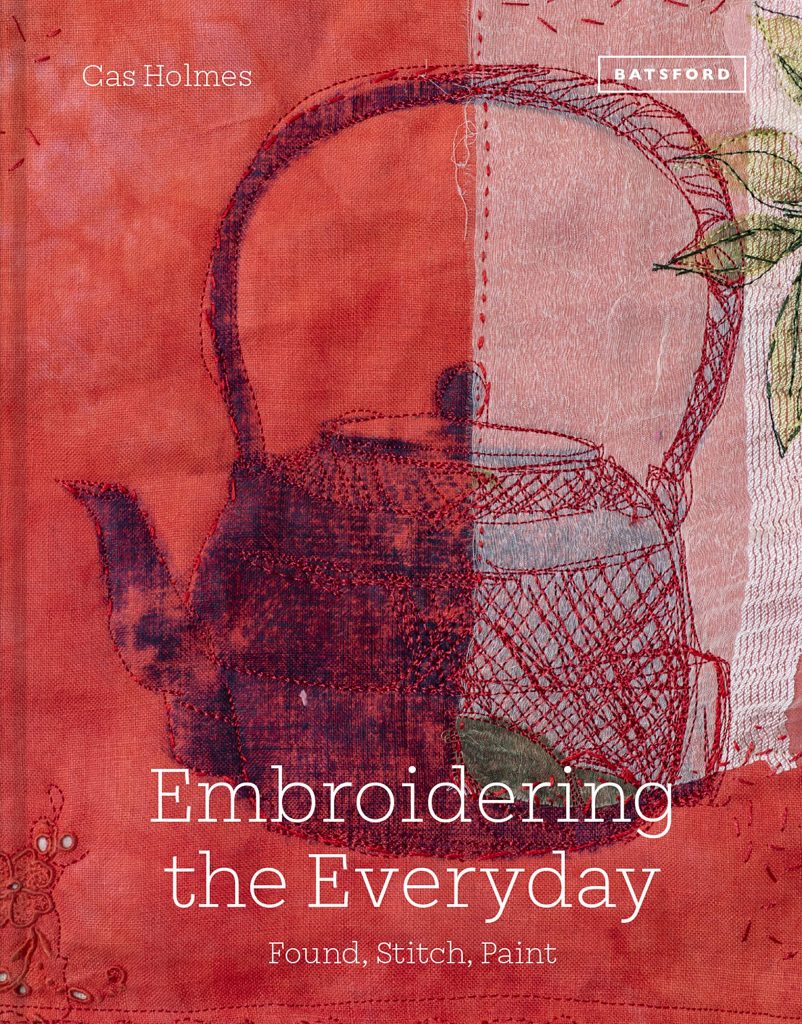

The most recent is Embroidering the Everyday, which was published in 2021. She’s an exhibiting artist with art textiles made in Britain and a member of the Embroidery’s Guild, UK and the Society for Embroidered Work. The stories and images to be found in the everyday and commonplace are a constant source of inspiration for projects and collaborations.

Gail: So thank you so much for joining us on this podcast. It's an absolute pleasure to have you and I know that the majority of the listeners will already know, well, probably more than you might like about you. So with that being said, for the few that I know won't, would you mind starting us off by telling us a little bit about how you first started to stitch?

Cas: Okay, so stitching didn’t come naturally to me. I perhaps denied stitch in my life when I was a youngster, simply because I never saw it around me or thought it didn’t exist around me. It was only later that I discovered that my mother knitted. She gave me a cardigan for my 50th birthday and I said, oh, that’s really lovely. Where did you get that? And she said, I knitted it, which was a complete surprise to me. I had no prior knowledge of those activities taking place in my home.

It’s as though my mother and my grandmother kind of rejected that part of their life, the textile part. And I did find out later that my great grandmother tatted and sent taking things around to people’s homes because she was a Romani, so it didn’t really exist in my life. I was always a painter and interested in art. My father was a signwriter, and it really was a painting that got me going. I was at art college. We were given these old paintings and drawings and other art pieces that previous students had left behind that had been salvaged by the art department to form the basis of our first project. Whether we were asked to work on an existing piece that had been discarded. And I had this painting. We had no choice. They were just placed in our little studio spaces. And I had this painting, and I didn’t know anything about media to that extent. You don’t get much of a training before you go to art college. And I started to try to work over the top, and this painting kept coming through, and I didn’t find it a very pleasing painting. I would probably find it pleasing now, but at that time, it was quite new to me, and in sheer desperation, I decided to rip off the canvas. And literally, I ripped it. And I thought, well, now I’ve got to do something with it. And I would actually say that’s really my strongest memory of picking up a needle as a process of repair. And that sat for a while. I started to work with paper and stitch paper. So really, my involvement with stitch was predominantly with what I would call painters materials canvas, paper, mixed media, and just using stitch as a means to break that surface and bring it back in that very fine art way.

So really, that’s where I started to stitch. If you like, other than stitching a button on, I could just about manage that. I’ve never been much at that time for doing very much at all with stitch. So, yes, that is my strongest. And I think that point where I had that ha ha moment, that needle and thread is quite useful for putting canvases back together. Yeah.

Gail: How did you progress from there to really coming to embrace stitch as its own art form?

Cas: Well, gradually, as I went through the art college, I began to be more interested in the substrates. I was working on at that time were predominantly, as I said, canvas or paper. But I began to look at how paper is made, and I think that started a lifelong journey into that idea of destruction and construction, which many people might identify with my practice of using found materials, I began to think about what those surfaces were and how they’d respond. And paper was much cheaper than canvas. Students never have much money. So I utilised what was there.

I recycled or reused paper. There was plenty of old paper left in the bin. So a form of paper making, not true paper making, because it was recycling paper, using a mould and a deckle and a frame to make the paper. And gradually, I got much more interested in what this stuff was. And I received a grant from the Winston Churchill Memorial Trust to go to Japan to study Japanese paper making. And that opened up a whole new world, because in Japan, paper has much longer fibres and I could see quite cohesively how it is being used in combination with what we would identify as textile processes.

So in the stencilling Katazome onto cloth and also woven into shifu or crumpled kneaded paper, mommy gammy that made kamiko paper clothing. And that perhaps was when I started to look beyond stitching with paper or incorporate more cloth into my paper pieces. Because initially all of my works was with either paper I’d made or with conservation papers or wet strength papers that I could stitch together.

Gail: That sounds absolutely fascinating. So can you tell me how the I suppose it's probably quite a long explanation, but what the difference is really between the paper that we would make here, perhaps the paper that I made for my city and girls course many years ago, and the kind of Japanese paper that you were talking about?

Cas: Well, I was very fortunate. I have a lifelong friendship with the former owners of Barch and Green and Company, which are the last handmade paper companies in this country that worked on a commercial basis. They made watercolour for the Royal Watercolor Society well over 200 years. I mean Maidstone was called paper making city. It is a town, but it was identified as that. So it was the home of good quality handmade paper. They used to make paper for banknotes and all the conservation paper.

So there are two basic principles and the Japanese identify them as tamizuki, which is our Western tradition. I’m talking about handmade paper as opposed to commercial. And perhaps the stuff you would recognize that many people have done in a liquidiser or pound it by with a mallet, as being the Western method. And most of Western paper is made with rags, waste rags. So that’s why the rag and bone man came round. So it’d be cotton or linen fibres that were broken down. And really in the mill, they were broken down with giant hammers, if you like. And the idea was to try to keep as much as a staple for the strength of the paper as possible. And that what’s made it good for watercolour paper. And that was actually made in a big VAT where the fibres floated. And when you put the mould and deckle, which is the frame that holds the paper into the VAT, you would pull it up once, shake it.

I mean, I’m simplifying, of course, and then it would be put on a felt and then another felt on top, so it was interleaved with felt. So essentially, that was the Western tradition. And the fibres were longer than you would normally find in machine made paper. But they’re nowhere near as long as the fibres you find in traditional Japanese or some other oriental paper, because it first started in China paper making. So that was adapted and you could always arguably say improved on in some areas with the Japanese as they tend to.

But so in Japanese paper making, they essentially one of the main fibres they use is from the paper mulberry and they use the white inner bark and the fibres are really long. So these are stripped down and then they again are beaten by mallet or by hand, but the fibres are so much longer. And then when they’re suspended in the vat, they have a mucilage added to them from the root of the toroyo AOE, which allows the fibres, leaves long fibres to suspend, but it also allows them to adhere to each other much more strongly. So that when you put the mould and deckle in, you might put it in several times as much.

Like if anybody’s made felt making, you know how you gradually build up the fibres? Well, that’s how that’s built up with Japanese paper making, so that mould and deckle will go under several times so that they’re kind of building up this web of paper to give it maximum strength. And then the crucial difference in the making of it is each paper is laid directly on top of another with no interleaving felts. And the only thing that separates it in the traditional method are one silk thread so that it’s slowly pressed and the fibres themselves hold themselves together better in the sheet of paper, where we need the felt to stop the paper sticking to each other. Though naturally, with this process, hold and the fibres in the Japanese paper are much longer. So you can see from try to shorten the explanation. But it is important to me that I explain that’s why that’s the substrate again, this is how it’s made. And that’s what fascinated me, why the paper is so strong when you use it in your own work.

Gail: How fascinating. Thank you for that. So I assume once the fibres, once the different leaves have all dried and the thread in between, then they would be separated.

Cas: Yes. And the old way would be to dry them on boards. So in Kurtani, which is a village, meaning Black Valley, where I studied, you would still see them drying on these huge boards tilted towards the sun. And most paper was made in winter by farmers, so it’s tilted towards the winter sun. But by the time I was there, in the mid 1980s through to the 90s, because I went back several times, they also had a metal stainless steel machine which had like a hot plate, not too hot, but warm enough so that had hot air running in it, like a big flat radiator. Really? So everything was flat and the paper went onto that.

Gail: What would they use that paper for? I mean, it's obviously very special, isn't it, when it's gone through that process?

Cas: Yeah, well, it depends. Different regions specialised in different papers. So I’ll give you three or four examples. So obviously there are more traditional uses for Japanese painting or writing. So these would have been the more common ground papers for long fibers. But in the same village, they made paper products, so they might be printed on using stencils and dyes and made into wallets or paperback. I mean, I’m not talking about the common paper bags. We dispose of paper bags that you can serve. I turned some dyed paper sheets into cushions, which I sat on for years at home with my sewing machine, at my sewing machine. And the only thing that gave way was my stitching, not the paper.

Gail: Oh, my goodness.

Cas: So it really is that strong. It really is that strong. Farmers used to wear clothing called kamiko. Kami means paper, and kamiko comes from kimono. Kimono means thing to wear, so it’s paper thing to wear kamiko. And they used to wear that, make this paper clothing. Sometimes it was treated with shellac or type of shellac, and the priests adopted that as a simple form of chinto, priests as a simple form of clothing to state about their simplicity and relationship to the life and world around them. Some paper was made with the fibres aligned all in one let in one way, and that would be cut to make thin strips, continuous strip, which would be spun to make shifu, which is woven paper cloth.

Cas Holmes’ Studio

Gail: When you talk about clothing, how could they wash them or how could they clean them? Might be more specific.

Cas: Well, that woven paper cloth, when shifu is made, it’s washed up to ten times before it’s sold, after it’s woven paper. I mean, if we consider the relationship between wool or cotton to make clothing and paper, essentially what they’ve done is actually just added another process.

They’ve made the sheet of paper out of these long fibres instead of putting them straight into spinning. But unlike a staple like wool or cotton, where you might twist it or twine it, particularly with wool, you might twine forgive me anybody who does work with weaving and wool, because I’m not trained in that area, but you actually twine your staples together to produce your strand. That’s my understanding. You might have three ply, four ply. When we knit with paper, it’s just a single strand twisted very tightly. And if it’s just used as a string, it’s just called cori. So I own a few pieces of this precious woven cloth, tiny fragments, because only eight people were left in Japan making it when I studied.

Gail: Goodness. Yeah. So it's very special and very.

Cas: Sure.

Gail: And I imagine very expensive because it obviously has a huge amount of time put into it. How fascinating.

Cas: Maybe that gives you that foundation that for me, the world of paper and the world of text, what we would recognize as cloth are not distinctly they’re intertwined, they’re not separate identities.

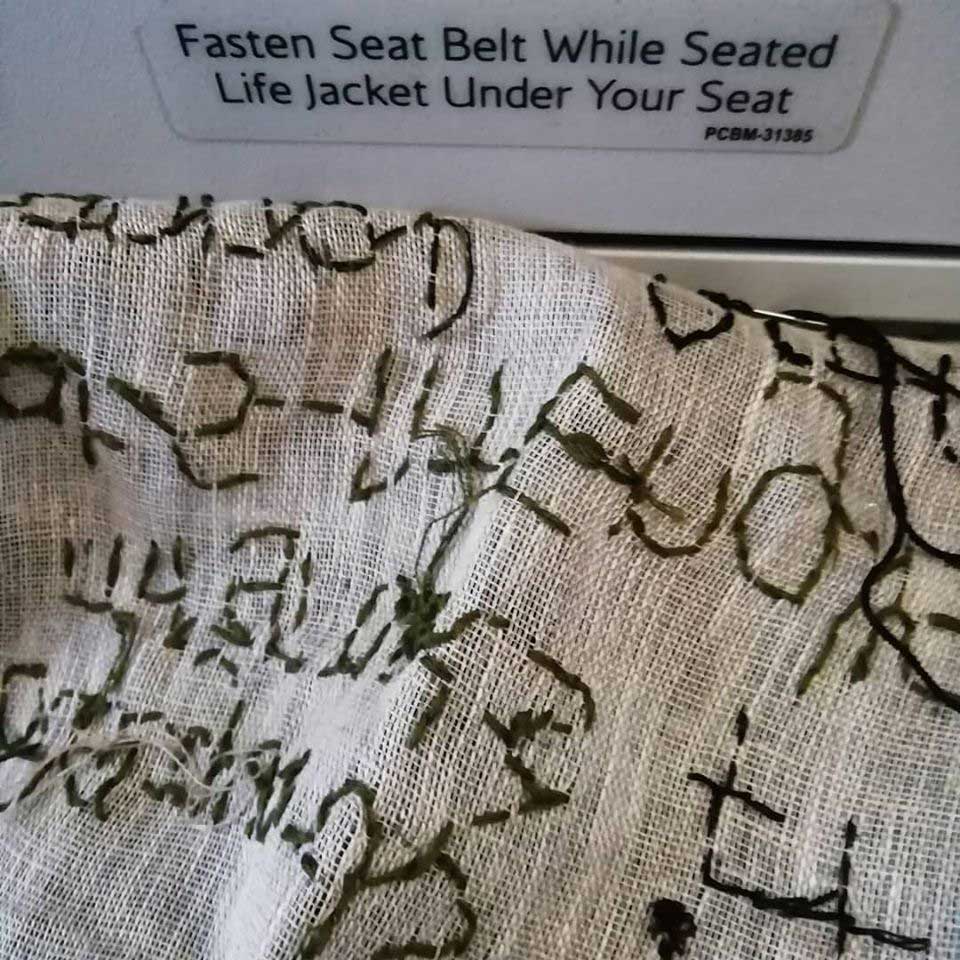

For me, they are just surfaces that respond in different ways and have a different feel to them. So some might be more resistant to being flexible than others, but you choose from that. And because I use found materials rather than evolve my own from particular specialist materials, that adds another element into what I call the unknowing side of my work. I like the fact that wherever I find a material, it will come with its own history in it, which will suggest what direction it might want me to take it and I have to learn how to work with it.

Gail: Do you think that perhaps not having that strong textile background from an early age and being coming to it more from the art and the paper making side has actually improved your practice? Perhaps because you don't have the same thoughts about what should go together, what should work. You've actually experimented with what you know, with what you already know, and that has brought out a completely different process for you.

Cas: I think you used the term improved my practice. I’m going to say it made what I did a little bit different as an orphan expression to do different, because I think that I was in awe when I did workshops with the Embroiderers Guild. It’s about utilising your knowledge and pushing it a different way. So I have a great respect for people who can make a beautiful traditional quilt and use the stitch and patterns in the way that they do, or somebody who works with gold work.

It’s about understanding what you want to do with it. So I would say that because I had a grounding in fine art and drawing, but also I think it’s to do with my cultural background. I come from a working class family and I just used what I had around me because we didn’t have much around us. I’d use my father’s. He was a painter and decorator, so I’d use rolls of paper that he had left over and some of his old match pots and things like that to paint with because that was available to me. And I’d only get stuff for birthdays and Christmases because there wasn’t the spare money just to go out and buy stuff. So my sketchbooks or drawing stuff would come at times a year that I wanted them or to use. But I didn’t know if I knew it at the time, but I think it was embedded in me by my grandmother and my great grandmother. They’re Romanies. So the idea of reusing what you have perhaps had always been in my background, and I maybe didn’t realise that as a child. But even when I visited my grandmother, there was always a vegetable garden.

Dad granddad, who married in, went out with her family toting goods, to door. To door, yeah. So she would have odd ceramics because he were either cracked or that on her, but still beautiful where they traded or bought things in the markets that she wouldn’t allow him to break up because often they couldn’t afford to store all of this stuff. But she’d always pick out some things that she liked to have in her home because she still valued them, even if they had a crack in them, because they looked lovely. So it’s about utilising what’s there. But she put all her energy into cooking. I’m certainly no cook, but I knew she had this. I only found out latently. She had those skills as a child from her mother, but I think it was about that time she just pushed away from it that more traditional role of working in textiles.

Gail: Yeah. And obviously crafts over the years have gone up and down. So some crafts I mean, I can remember the phase on Macrame and now it's back again. They're very cyclic, aren't they?

Cas: Yeah. And I think when you talk about know, there’s this kind of thing about craft and art, all good artists need to be good craftspeople. What I mean by that, they need to develop a relationship and understanding of how they want the materials to work and what they may want to do with them. And I’m using the word may because it’s also that willingness to step into uncertain territory and experiment that I think is the key division. Experiment. I’m not saying that people don’t experiment with colour or composition when they’re in the craft, but it’s also to do with functionality and doing something that’s about expressing an idea as opposed to it being a thing in itself.

I mean, these are broad definitions and please don’t it’s just me still trying to get to grips with this whole debate about art and craft. And I think some painters who just continue to do the same thing all the time and getting the same results are in the same position as most a lot of people who might position themselves as craftspeople. And there’s no right or wrong about being either or. It’s about what your intent is with the work that perhaps defines you as an artist, what is your intent. And it certainly is about expressing the things that I care about in the world around me or about the materials itself, as opposed to thinking about making a product.

I’m always thinking about what am I going to do? How am I going to investigate what’s important to me and how are those materials going to help me discover what that is saying I am going to make it’s going to be what am I going to discover through asking the questions about my own practice?

Gail: Well, I know from our students that and obviously from myself, that once you actually start to put up those end results, in a way you've erected a barrier because you've then limited what you're going to do and how you're going to get there. If you can look on it far more experimentally, then I think that's where some of the really innovative work tends to get done.

Cas: Yeah, and it’s not easy. I’ve spent 40 years of doing stuff that I don’t find easy. It’s challenging. There are days I kind of particularly now, as you know, my circumstances have changed. I’m working a lot more from home because my partner had a stroke. It’s much more challenging.

I’m not out there in the world as much as I would be able to, normally stimulated by that interaction with other people in a studio, but it can be rewarding. And when things start to appear and you begin to understand what you might be doing with the thing that you’re investigating, it can lead to other development. But I am notorious for saying that one of the biggest groundings I have is also the idea of looking and drawing. For me, it’s a foundation. That’s what I started to do very early on as a child, and it’s the thread that’s run through all of my work. It may not always be apparent in my outcomes that people in the fact that they’re cloth and stitch, but I always argue that what I’m doing is I’m just using the nature of those materials to express what I understand about looking and drawing.

Gail: When you're actually creating a piece, how much planning do you actually put in beforehand? Or does everything develop organically as you move along?

Cas: They go side by side. I don’t pre plank. That idea of destroying that canvas and investigating what material does has stayed with me. I have endless research folders from early on, and I still keep them several different types of sketchbooks. Some are basically what I call a reflective practice. So when I’m working on something, I will stick things in, I’ll make notes, I’ll talk about what I’ve seen, I’ll maybe do some sampling. Not necessarily that piece is going to look like that, but just to get to grips with what the materials can do or something I might have discovered.

The best things often are things you discover as happy accidents as people might call know. I think it was Picasso said, all artists make mistake, but great artists know which ones to know. So that whole idea that something might happen, you think actually there’s room in developing that with what prior knowledge I have and what I might discover. So I’m not saying they’re going to be groundbreaking things you’re going to make the next because you’re always building on what you know. But it’s about keeping that moving. And I always have several things I’m working on at the same time so that if I get stuck on one, I can park it and then I can go back to it. Afresh.

Gail: I think that's actually a really good practice for it's something we often suggest to our students that because you can get very fixated on one element of something that's not perhaps going very well, sometimes the best thing you can do, I think, is walk away and perhaps turn your attention to, I don't know, off the top of my head, knitting a pair of socks and then return to it after you've had a little bit of thought.

Cas: And also, sometimes it’s not always good to work. It’s harder up for me because I’m not saying it’s harder for me than anyone else, but I recognize how hard it can be now that I’m in a role that I mean, obviously I was working and teaching, but teaching was always about that cross exchange of information. Now that I’m caring, it’s harder to carve out those pockets of time to develop my own practice as well as keep up with all the additional tasks that lovely Derek used to do in the house.

I’m painting a window at the moment because it needs doing, but while I’m painting that window, ideas infuse in my head. When I’m going out on my hours walk or cycle, which I try to do, I’m never more than 15 minutes away from home, so I’m not abandoning him, I can get home at any time, but I do know I need to keep myself well and fit. So being out in the world every day, I like to be outside, that’s always been something I want to do. So I go out for a walk or a cycle every day. But that’s sometimes when you’re having this time out of that space you normally work, that you allow the ideas to seep through. You might see something on your walk, or you got that quiet space that you often need. You may not recognize you need it, but that’s sometimes when things spark up.

Gail: In my mind, yes, I would absolutely agree with that. I think that the moment, if you can just accept that you might not come to whatever answer you're looking for at that moment, you need to walk away and come back. And I do think because a lot of textile art is very obviously very time consuming, we spend a lot of time working on different elements of it, then you can get very fixated on one element. Sometimes when you back off and you look at that element as part of the whole, it doesn't seem anywhere near as bad as it did when you were just concentrating on it.

Cas: Yeah, I’ve often gone through making nearly the whole thing and then pulling a whole section out of it, rather like a painter will paint over a piece. And I think that’s what sometimes people might fear doing, because they’ve invested time and they think, well, that’s my valuable time, and I can’t do that. Well, if it’s not working, you haven’t lost time, you’ve gained understanding.

Gail: Yes, but I absolutely agree with you that people are very unwilling to do that. They see it as well, perhaps a bit of a failure. They also see it as a loss of time, maybe a loss of money, because, of course, if you're abandoning something that you've paid for the materials for. So I think there are all sorts of reasons why people don't want to do that. But I agree with you. It is experiential learning.

Cas: Well, there is a little Oriental. It might be Chinese or Japanese. The interchange between cultural stories, between those two cultures is phenomenal. And I’m probably going to mistell it here, but my memory of the story is that a painter was asked to create a painting of the Emperor’s favourite horses. And he went away for a year and a day and returned later. And he came with this beautiful ink drawing of the Empress horses that captured the character and the flow of the horse and presented the Emperor with his bill. And when he presented the emperor with his bill, the emperor’s eyes raised at the bill and said, but that’s only one drawing.

And then the painter clapped his hands three times, and in came 100 workers, each carrying 100 paintings. And he said, this is all that I’ve done in order to achieve that. And I think when people also raise a question about the value of things that are handmade and we all know that often you’ll see a price of a painting, yet we fight really hard to achieve even a reasonable return for our work as textile artists. That it is the work that’s unseen has enabled you to make the work that people think is as effortless.

Gail: It's very true. And I think that sometimes people see beautiful sketchbooks, perhaps, that someone has put online. They look at them, they feel really despondent because they think, well, I'll never produce anything like that. But in actual fact, many of those things are the product of a huge amount of other work that has come together. It's one of those anomalies, isn't it, that unless you actually do some form of textile art yourself, you don't appreciate the work that's gone into it?

Cas: Well, that would go for any practice, whether you’re a dancer, a musician, a gardener, to achieve your vision. I’m not talking about testing it, that it’s somebody else’s idea of what’s good it’s to do. What you want to do with your materials takes an awful lot of work. I’ve got to stage. I don’t really care what people think about. I’m a harsh enough critic of my own work, so I don’t need anybody else.

Gail: No. Well done, you. That is actually, I think, one of the probably the best pieces of advice that you could give to anyone.

Cas: I don’t think I was always like that. I’ve just got so much going on in my life recently, but that’s been for the last 10 or 15 years. I thought, I’ve just got to do what I need to do.

Gail: Yeah. So how do you go on, Cas? Do you take commissions? And if so, how does that sort of ethos play into the commission process?

Cas: I do take commissions. They find their way to me. I think I am good at communicating, I’m good at knowing what works for me. I have an online website which has a Shop page, which I update now and again, which has mostly my smaller works on. And I do have some pieces on the Saatchi website. I’ve never actually sold anything directly from there, but a lot of people have seen what I’ve done and I’ve asked, would I do or I like that piece of work, would you prepare to sell it? I tend not to post.

My bigger pieces work up and say they’re for sale, but they’re up there and if people are interested, they can contact me. So I’ve worked on several commissions. I did one during the pandemic for a pastor and he wanted to base the piece on I don’t know if it was the 23rd Psalm, I’d need to double check, but anyway, it was to do with a piece of religious text and it was quite a large piece and a large commission. I was thrilled to get it during the pandemic, I can tell you. It certainly helped at the early stages and sent me some pieces of material. That’s how I like to work.

So a lot of times when I’m working on a commission, I ask people if they’re prepared to send me either photocopies or some pieces of cloth or material that they would like me to consider to be incorporated. But usually they give me an idea of the scale and the cost or maybe where they want to hang out. But I’m left to then work on it and I’ll send them an update. But I don’t do a pre designed drawing because it will never turn out that way, because as I’m working, I hear the voice of that person and the person they want to gift it to, or remember it, remember, come through, touch wood. I don’t think I’ve ever had anyone say, well, this isn’t what I expected to thrills. But I think that’s always a worry, isn’t it, when you’re working to commission? This wasn’t what I wanted.

Yeah, but I think it’s because I’m quite clear that you’re entering a dialogue with me and you’ve seen something you like in my work that you’ve asked about to be as part of the commissioning process. And for me to be able to have that response to your commission, I still need to build in a bit of freedom about how I might respond to the materials you’ve given me. Sensitively. I’m not just going to just take them and put them together, but thinking about what we’ve discussed so that it becomes a gift back to them, if you like, rather than matching their furniture. That’s quite a different commission. To some corporate type, commissions can be much more to do. I’m not talking about high end corporate commissions.

I mean, Alice Kettle‘s just had a fabulous exhibition in London with her corporate partners where it’s about, again, that expression of her ideas which they were really interested in. But you can buy commissioned work that perhaps works better with your furnishing because you’re much more interested in the design of your space, let’s put it that way. And there’s nothing wrong with that. It’s just a different way of working. But I don’t work in that way. I’m not a designer, I’m an artist.

Gail: So you obviously were mentioning there the pandemic. And when I've spoken to people about that time since I think many artists and craftspeople during that time either found it an absolute nightmare and I know an awful lot of the population did, or they found it actually very helpful because it gave them a lot of time to concentrate on perhaps developing new things, new ideas. How did you find that period for you?

Cas: Mixture of both. Initially, the first two or three months was quite really hard because I would say it was hard for everybody, regardless of what job you did, if you’re a freelancer, to see the world that you understood, your work dry up, everything deferred till some indefinable moment in the future working in place.

I mean, I did a lot of workshops and they were all over the world and they were cancelled there and then there was no choice, so that meant income dried up and I had a pattern of life where I worked away and then came back and suddenly it all changed. So the first two, three weeks to a month, it was just fight or flight. I just had to email my partners, get things sorted. I went out for a walk just to calm myself, because although it was quieter, I think it was a very tumultuous time for everybody suddenly to have the world that you’re familiar with withdrawn from you.

Gail: Oh, absolutely. I think we were all actually, particularly during that first lockdown, we were all scared, weren't we? We were seeing on the news every day of what this disease might do, what the repercussions might be, both obviously physically on people cells, people we know, and also from a financial point of view for the country. It was a really scary time.

Cas: And so then gradually things started to ease. My adult education centre, even when it came back after April, we were on Zoom, probably before the colleges were, and students were a bit reluctant to begin with. I did a couple of test sessions to begin with over the Easter break, and I was only working with a phone and a tablet because my equipment here wasn’t set up for that. Then my PC wouldn’t have connected. I was up two floors, so I only had WiFi. It wasn’t hardwired in, so I couldn’t rely on that. I had to do it on my phone and a know everything for everybody was until things sorted out was a little bit had up. But I set up a group called What We Miss, What We Value, which you can find on my Facebook page. It’s a closed group, but I set up projects with them which anybody can look at and have a go at doing. There’s no income stream from that.

I set it up because I felt it was relevant for connection between artists and makers and enthusiasts and people who were my friends, if you like, who I knew. But I made it a closed group after about a few weeks because the membership numbers were just getting too big for me to really feel that was doing what it needed to do. But it’s still running. But this page I have on my website, people can look at the project if they want to do it, they can do it or not. So I did a lot of things voluntarily online because I felt I thought I might stitch scrubs, but I thought, going back to my earlier story, I thought there’s no point. What point? Me stitching scrubs because it would take me forever. I can make improvised clothing, I’ve done that. I can improvise things. But following a pattern after about two, which would take me all day until I got more confident with, I thought, that’s not the best thing I can do.

So I started to do some things that people could engage with for mental well being invited by Westine College to do, which I did for them gratis and how to work with the sketchbook. Just some gentle things that help my community, if you really but in doing that, I also began to hone my skills, which, thank heavens, I did, because I’m able to balance a little bit of my practice. Now, I’d love to be out there in workshops, but I can’t stay away overnight at the moment, so that’s really hit a lot of my practice. But I am doing some work overseas by working online with invited partners. And that’s one of the things I’ve always been clear about. I’ve worked with partners that I already had in the past because for me it was about supporting them as well as supporting me, rather than running my own workshops independently.

So I’ve always worked 40 years I spent working with partnerships and I felt that was very relevant. But also it was about that trust you have with those partners. So that now I’m working more online. I’m not doing anywhere near the level and amount of teaching I used to do before my partner had his stroke. But I’m doing enough that I can manage. And on the knowledge that I’m quite clear that he has to be my priority. And if I have to stop, we just catch up some other time. And people have been incredibly flexible and I think that’s what I gained from the pandemic that resilience and the ability to learn from not just the practical things. I’m a whole world away from where I was online, although I was pretty reasonably confident, but now but also being able to recognize that there are different ways for working.

Even before we knew about the pandemic. Whenever I went into a workshop, because I had worked for a long time and still do, within the care services with hospitals, with mental health, I was very careful at the beginning of any workshop to say, I’m here to share my skills with you and for you to get the best out of this. I want you to be mindful of how you are and how you’re feeling. So if at any time you need to step out, just let me know and step out because you don’t know how you are going to respond. You might have something going on in your life. And these are things that people may not feel comfortable talking about. And we’re all getting old. I kind of just discussed that because I think that in order for us to be creative, we also need to be mindful of us as a whole person. And if you’re trying to work through and you’ve got a steaming headache, well, don’t work through.

Gail: Yes, absolutely. And you'll never produce your best work in those circumstances. So it's just better, I think, to admit that you're not 100% step away for that moment. Then when you go back to it, you'll be renewed, refreshed, and hopefully ready to continue with that creative process.

Cas: Yeah. And I don’t need to give people permission to do that. But expressing that in a workshop or any situation where I’m working in collaboration with another person and being direct about it gives people the space to be able to do that for themselves because they might feel they can’t do that.

Gail: It does. Because I think a lot of us are still certainly people of my age, older, are still sort of very much of the mindset that this is a formal learning environment. And you've paid and you've turned up and you've taken a place, and you have to stay there, and you have to get the most out of it and do the best you can. And unfortunately, putting those constraints on yourself often means you do the opposite.

Cas: Absolutely. And I’ve thrived within that teaching and learning environment because the teacher learns by observation, body language. That doesn’t mean I’m out there spying on people, but that’s what I actually miss about being in place.

I try to talk when I’m teaching here in my studio space, I talk about removing that screen so it’s as though they’re looking at a window, but it’s still there. But it is try to making it as informal because that’s what zoom is, as opposed to a pre recorded. It’s about that informal connection you have with students in a workshop where you can keep a weather eye on what they’re doing, which means you’re still working, but knowing when to step back and just, she looks okay, I’m going to walk past because sometimes people don’t want you saying are you okay? They just need to get on with what they’re doing. You learn those skills when you’re in a workshop, but also that exchange and honoring the student’s own experience in the workshop, which is equally important because I’m not daft. People come to my workshops who’ve got incredible skills.

They may be artists in their own right. I don’t know what that background is sometimes. Sometimes I do. And when I you know, I remember one of my first major workshops was in Germany and the people had signed up. I looked at the list and I thought, My God, these are my colleagues. When you say, I always think I enter a workshop. It doesn’t matter what level of experience with a bit of stage fright anyway, because you’ve got to perform yourself as an artist. So it’s a two way process. I’m confident in my own skills, but I’m also human. So anything that happens in a workshop, happens in a workshop. And people get as close as they can to my practice as part of that process.

Gail: And I think the process for teaching has changed over the years. I had a wonderful professor when I was doing my well, my master's and my PhD, actually, Andrew Satville. He's actually sadly passed away this last couple of weeks. But he always used to say, we've moved away from the sage on the stage to being the guide at the side. And I think it's a very true way of actually portraying how teaching has changed because it's no longer a case of just getting up there and talking at people and expecting them to do exactly what you say, is it? It doesn't work like that now.

Cas: No, it doesn’t. No.

Gail: The next thing, if I could, is to ask you about your new role as a carer. I know that obviously you've touched on it on a couple of occasions, but it would be really interesting if you could just tell our listeners something about it, how it's affected you and how you've managed to keep working, really, at the same time. Because I know it must be both well, obviously challenging, but rewarding as well. And I also know it's an experience that many of the people that listen to that will have in their own lives.

Cas: Well, I think to such an extent that I think you probably received the email and it says Artist/Carer now.

Gail: Yes

Cas: I try not to over reveal the day to day life, but I want to make that very present in my practice because I become with over. I think it’s 11 million carers in this country either doing certain level of care. It’s not a tribe or a group that I would have chosen to belong to, but at some point, we are all carers. Whether you’re caring for children, you might be caring for older parents, even if it’s just going for shopping to a greater or level or lesser extent. We all have a caring role. We all pick up those things on a day to day basis, whether you’re preparing food for someone in your family.

Derek used to go and paint the windows every two or three years. He’s caring for the house and making certain we’ve got a safe place to live. So as far as I’m concerned, being a carer means there are other elements to that role which I’ve had to learn quite quickly and often. It’s been incredibly difficult. And some of the difficult things are the minefield of paperwork and organisations which because of so many things being devolved from social services to charities at the first few weeks Derek was home I found it really hard just managing day to day because he was so much more dependent then really dependent. And also agencies coming in, paperwork to be filled out.

I was just overwhelmed with all of this new language, a new skill set that was actually being just offloaded on me so very quickly. That was quite as scary as those first weeks of the pandemic work was. That didn’t touch the edges compared to my first few weeks of Derek being home.

Gail: Mean as somebody that cared for not a partner, but both parents, I do know exactly what you mean. And as you say, sort of the actual day to day, hands on caring is one thing, but all of the organisation and the paperwork and the frustration that goes along with that is quite another.

Cas: It is quite another. So I’m going to just park that and just talk about a little bit now about, I want to say pros and cons, but I’ve learned a lot about myself. I mean, I talk about the fact that we are both stroke survivors because we talk about stroke survivors and I think it’s important that we do that, but it actually impacts everybody around the person who has had a stroke or has a heart condition or any other illness. But there are other things that I’m sitting in a home that he’s created, the studio I work in. He was putting the window in three or four days before he had his stroke, right?

And that was finished again during the pandemic. I was fortunate. We had this house with a gardener. It’s only a little house, but it’s my home from home. It’s a safe place to be, if you like, where many people didn’t have that. They were in a flat with children and no gardens.

Gail: Absolutely

Cas: Although I find it tough. We are managing. He built an extension a few years ago and that’s where his bed is downstairs, so he can access the garden. He walks with a stick so he could access the garden, get around reasonably okay. He’s not able to work. His left side has gone. So that means I’m doing a lot of things during the day, like cooking, assisting him when he needs it, learning to step away when he doesn’t. That’s really an important lesson to learn.

Gail: That's difficult, isn't it?

Cas: Sometimes it’s harder to do than you think, because you’re just looking and you’re thinking, oh, no. But if he has to fall, he has to fall. It’s an unfortunate part of being slightly mobile when you’ve had a stroke. It’s that managing how I interact with him. He’s been phenomenal, he really has. But he’s not going to be climbing ladders or painting or doing the stuff he does anytime soon, if at all. But the fact he’s mobile was a miracle because I didn’t even think he’d get to that stage. It was devastating what happened to him. No mobility, virtually no vision.

Gail: So there's obviously been a huge improvement from the initial stroke.

Cas: Oh, yeah. It’s still a profound stroke. But we didn’t think he’d survived, to be quite frank.

Gail: Yes

Cas: So I’ve learned to adapt and work around my new life, our new life. And I will admit, thinking about taking on less work before the Pandemic, I felt I was in that position, I could do that and concentrate more on my work and also just continue to work for some of the organisations I wanted to, because I’m in my 60s. You get to a point where you’ve got to focus on what’s right for you and if you can afford to do it, this wouldn’t have been the way I chosen to do it again.

Gail: I understand what you mean.

Cas: Yeah. But it’s taught me a lot about myself. I do a lot more gardening and that’s influenced how it’s influenced a lot of my new work as well. This new relationship I have with the house, with Derek and the garden, has influenced some of the things I’ve been working on for forthcoming exhibitions about our interaction between brain, mind and body and the outer world. So it’s still evolving, it’s still raw work.

And I’m often showing some of these new I mean, I’ll be showing some of the first responses to that at the Knitting and Stitching show in October with art textiles made in Britain. And so that’s the other piece about being adaptive, if you’re honest with your partners. I have been absolutely overwhelmed and surprised by the kindness of people. Yes, I have an exhibition in Scotland at the moment, which I cannot go to, but we have worked via Zoom. We’ve built a huge program, got funding for it to support the local community. Schools have responded, the cost, Scottish Potters responded. And whilst I would love to be there, the kindest thing that the organiser, Claire, had said about her involvement with me, she said, this wouldn’t have been possible without you and your involvement.

And this is just a testament to what can be done and what we have learned and what skills can evolve from not necessarily having to be in that place. And they have come through both the Pandemic and my situation. And I have a great deal more respect for how we might be able to reach out to communities who otherwise might not be able to get to places because of restrictions on their lives, such as I have.

Gail: Absolutely, yes. I mean, so much more has gone online and obviously the pandemic has only hastened that process, hasn't it? And I think some people complain and say, well, it was so much better when you could go to a shop and see a selection of things, when you could go to a gallery and see an exhibition, but there are upsides to it as well, and obviously that's very much one of them.

Cas: Yeah. But I think both can coexist. We yet to find a balance. I’d be the last to say. I mean, I’m doing my first workshop in place since last year, since August last year at West Dean in September. It’s one of the things I’ve managed to keep going and I want to, because it’s a lovely place to work.

I’m not saying all my other partners I love working with, and they know that, there’s no doubt about that, but they’re totally understanding and it’s really hard to all the carers out there, my hat goes off to you because I’ve only been doing it for two years. I know people have been doing it for far longer, but just to get a night away is just so hard that I can’t work. Then Derek’s brother is flying over, so I can get away for five days. I try to do one thing a year where I’m in a studio with people, because I actually need that for my intellectual wellbeing, not just my physical well being and my mental wellbeing.

I need that intellectual side of my work to keep going and to be with people who will challenge me with what they do and how they respond to a workshop situation. I’ve thrived on that. And that’s the thing I actually miss the most, is being in place with people.

Gail: Yes. And that intellectual stimulation that comes along with that, I can completely understand that. And I'm so glad that you've managed to find a way through, because it must have been incredibly difficult.

Cas: Yeah, well, it’s ongoing. I’m not going to say when people say how’s it improving, it’s going to be ongoing. It’s not something that you can give a timeline to. No, I’m sure timelines could work in two ways. I’m just accepting every day I have now, rather than I’m planned for the future. I’ve got projects planned in the future, but as I mean like with art textiles made in Britain. My group. I’ve done a lot of some of the background work but they have been incredibly supportive and understanding and still want me to be part of the group because we are a small group and we are a supportive group and I’ve managed to get some cover so I can help to hang and hopefully go to the knitting and stitching show in Alipalli. I can’t go to Harrogate, but I can get to Alipali because that again is a place where those treats, if you like, of going to an exhibition.

Gail: Of few and far between and being able to look at all the obviously some of the work that's been done, but some of the things that are for sale. It's just a lovely place. Anyone that's interested or working within textiles, it's just a really lovely place to go.

Cas: Yeah, it is. And I’m so looking forward to it.

Gail: Obviously. I know that you've talked about a couple of things that come next, but is there anything else? I know that you're quite a prolific author. Are there any books coming up or what's on the horizon?

Cas: All I can say at the moment is I am doing some writing for various projects, but I can’t talk any more about that at the moment. Until any publication or writing that I’ve been doing has gone to bed. If you like, has been accepted or put to bed, then I start talking about it because again, it’s to do with my current situation. I don’t know if I’m writing or doing a project until it’s ready to be launched.

I don’t feel comfortable talking about it in case it doesn’t happen. Yes, and I think that is the wariness that came from the Pandemic because it took as much time, it was a lot of hard work. I’m picking all of that and then rebooking and then unpicking again that now I dark kind of whole things have all confirmed.

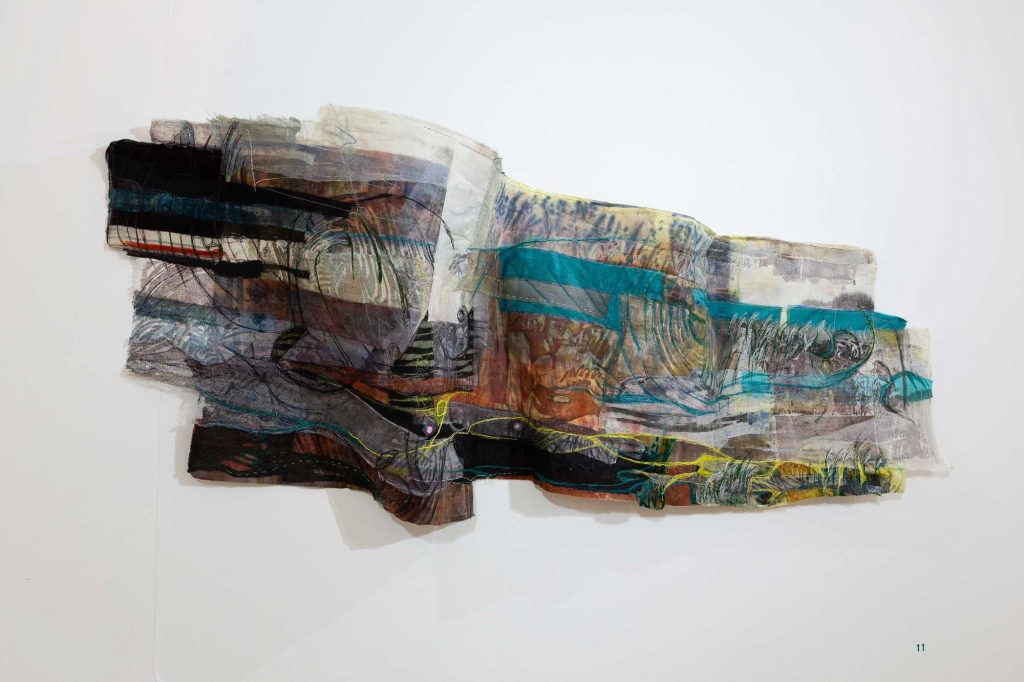

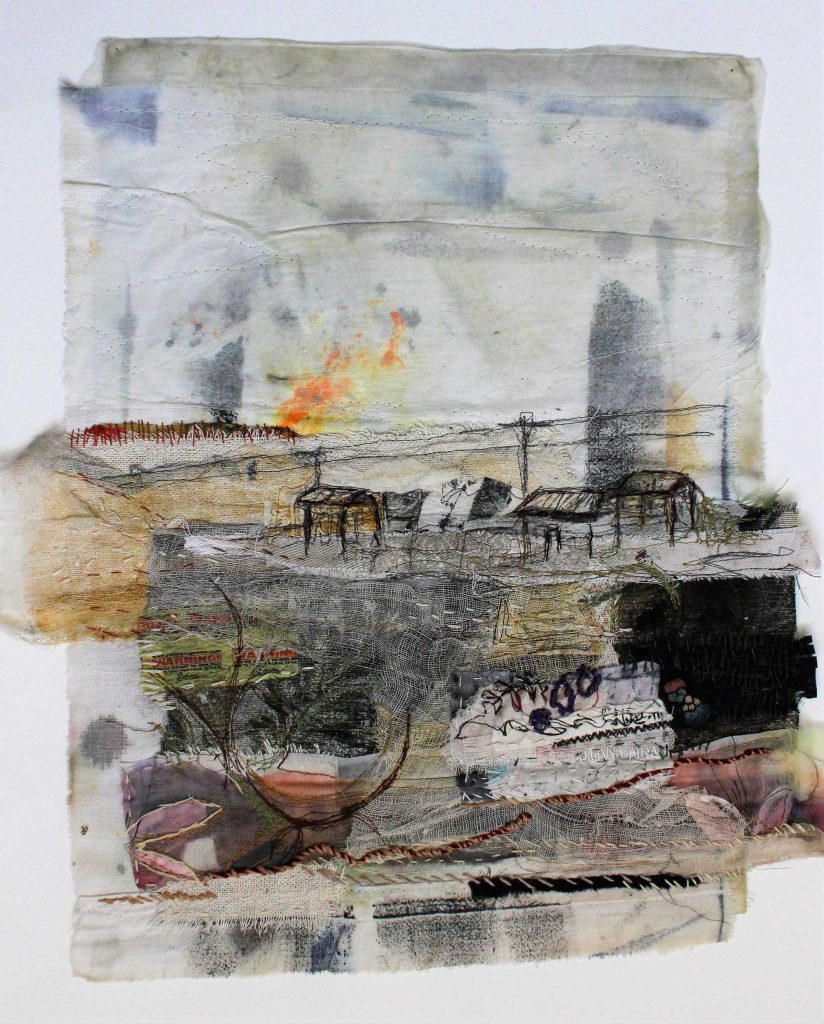

I can talk about two projects, three projects I’m working on at the moment, which is the exhibition Places, Spaces, Traces is touring. It goes to Queen Street gallery in Neath in October the end of October, early November and it’s currently on show at the Barony center with Craft town Scotland until the 7 October. All this information is on my website anyway. And this is an exhibition that started and was supposed to start at Antwerp in 220, but it actually was exhibited in 221 because of the Pandemic and was first filmed at LV 21, which is a light vessel in the river Medway. So this has been ongoing for the last two years and different communities have responded to it. So each iteration of it has changed.

The shipping forecast, which is the main exhibit of my work, which is the core exhibit in the exhibition, remains the same, but the other exhibits are a response to that in very much the same way. It’s all to do with about the migrant community or our sense of place where we think we belong. So that your sense of who you are and what you do can change according to the situation and environment you’re in. I believe that strongly. Your core, who you are is still there. But you change as you go through life. What you were doing a few years ago might mean something else now. Oh, you do?

Gail: Absolutely, yes.

Cas: Yeah. So that is touring. I’m working on a project called Storytellers with Kent Creative, and that’s an exhibition of various artists, painters, printmakers filmmakers. I think I’m the only textile artist. And they’ve identified people who use the power of storytelling in brackets, if you like, communicate an experience or a story through their work. And that will be at the Beanie, which is in Canterbury from December.

I’m very pleased to have been part of that. There is a little video. Again, the links are on my pages that tells you a little bit about that work. And I’ve also been engaged by the Romani Cultural and Art company for their celebration of the 10th year of Romani Cultural and Art Company Gypsy Maker project. I was involved with Gypsy Maker Four, which toured, but was grounded because of the pandemic. So they will be showing past Gypsy Makers work plus new works commissioned bias. And I’m recycling some old work into new work because a lot of my projects is about recycling a lot of my old work into new work, which seems apt because it’s about repairing. A lot of the work I’m doing is about repair. There’s a connection there with Derek’s Brain and our know, the idea of reparation. And then the final thing is, as I said earlier on, the Illuminate with the art textiles made in Britain.

Gail: So, Cas, it has been an absolute pleasure speaking with you today. Thank you so much for taking the time. I know that you're a very busy lady and I really appreciate that you've taken the time out of your day to speak to me and obviously to the listeners about this. Thank you so much.

Cas: You’re welcome. You’re very welcome. And it’s been a pleasure.

Where to find out more

You can refer to the publications by Cas Holmes including Embroidering the Everyday. In this book Cas invites us to re-examine the world and use the limitations sometimes imposed by geographic area or individual circumstances as a rich resource to develop ideas for mixed media textiles in a more thoughtful way. With techniques and projects throughout, the book explores:

- How to be more resourceful with what we have to hand, including working with vintage scraps, homemade dyes and papers, and even teabags and biscuits.

- Rediscovering family history and how photographs and objects can provide inspiration, including Cas’s own exploration of her Romani heritage.

- Drawing inspiration from our local landscape and how it changes through the seasons.

- How to transform materials with mark-making, printing, image transfer, collage and stitch.

You can visit her website at casholmes.com to see more examples of her work. You can also follow her on Facebook and Instagram

Workshops and current news can be found on her blog.

Images:

Rikard Österlund (Painting with Cloth Exhibition, studio images by Sheilagh Dyson and author, all other images by the Author.

One Comment

Thankyou for such a thoughtful interview process. Transcript gives a good sense of content. Hearing our engagement in the flesh is so much better. For those who may not know, ‘Alipali’ is not some ‘exotic’ place It stand for Alexandra Palace, affectionately known as Ally Pally. It is where the Knitting and Stitching show is held each October.