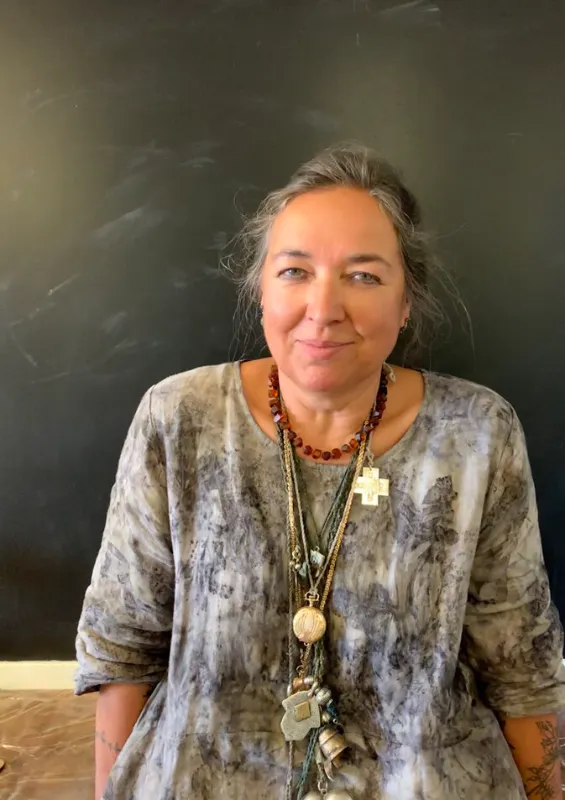

Australian-born Textile Artist, India Flint, is renown for her ability to weave nature’s tapestry into her creations, allowing the delicate beauty of the natural world to permeate her work. With a captivating style that combines eco-dyeing, botanical alchemy, and slow stitching, Flint has established herself as a pioneer of environmentally conscious textile practices.

Her work always reflects her passion for sustainability and eco-consciousness, reflecting her deep commitment to preserving the environment. Flint sources her materials ethically, often foraging for plants and utilizing recycled fabrics, aligning her practice with the principles of slow fashion.

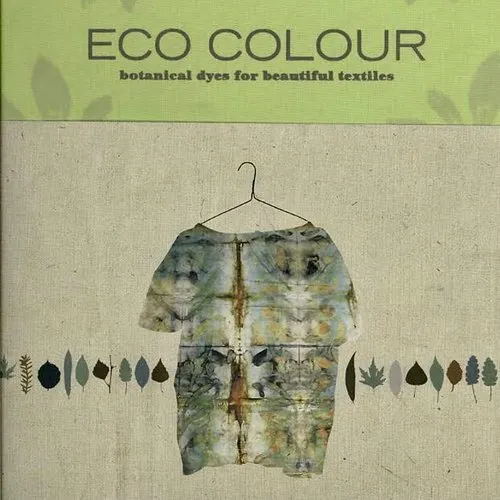

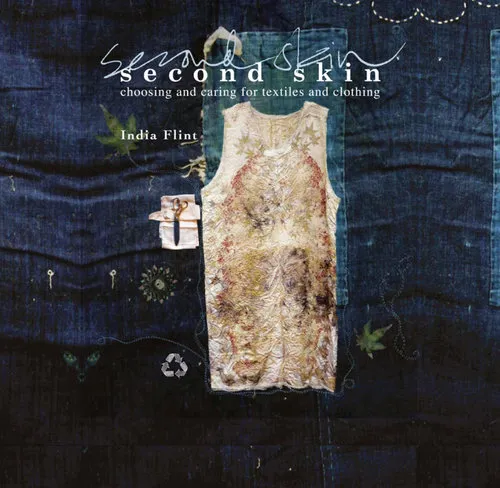

Flint’s artistic achievements have garnered global acclaim and recognition. Her works have been exhibited in renowned galleries and museums worldwide, captivating audiences with their ethereal beauty and thought-provoking narratives. Additionally, she has authored influential books, such as Eco Colour: Botanical Dyes for Beautiful Textiles, which have become essential resources for aspiring textile artists seeking to explore sustainable and eco-friendly techniques.

Beyond her artistic prowess, Flint is celebrated for her dedication to sharing her knowledge and empowering others. She conducts workshops and masterclasses around the world, inspiring a new generation of textile artists to embrace eco-dyeing and sustainable practices. Her teachings have fostered a sense of community and collaboration within the textile art world, fuelling a movement towards greater environmental consciousness and creative exploration.

India Flint’s transformative artistry, characterized by her unique style and eco-conscious approach, continues to captivate and inspire. Her achievements and contributions have not only enriched the field of textile art but have also sparked a global conversation about the importance of sustainable practices and our intrinsic connection to nature. Through her art, Flint invites us to pause, marvel at the wonders of the natural world, and embrace a more harmonious relationship between creativity and the environment.

India Flint

“Eucalyptus is decidedly my first love as every part of this genus will yield some kind of colour…and the range is astonishing, from green and yellow through gold, orange, tan, rust red to brown, black and even purple.”

What are you working on at the moment?

I’m in the midst of filming for my new online course ‘bagstories’ (for the School of Nomad Arts) that sets sail (dog-willing and with a fair wind) on the coming solstice. It follows (and to a degree supplements) ‘tidewanderings’, a course that grew from a dress I designed for Maiwa, the sustainable dye and clothing company built by Charllotte Kwon primarily to save crafts that were threatened with extinction in her beloved India.

I frequently taught for the annual Maiwa Textile Symposium before the Great Plague, and our work together has grown into collaboration from time to time, sharing ideas about clothing that can last a lifetime. I don’t receive a commission from sales, that’s not what this is about for me, it’s more the delight of seeing my clothing realised and made available to like-minded souls around the whirld. The ‘tidewanderer’ dress is an ode to my late maternal grandmother and students can follow the making of a hand-stitched version (upcycling pre-loved garments) or invest in a hand-woven linen version sewn at the Maiwa studios in Bagru, India.

What was your journey to eco dyeing – how did it all begin?

I have my maternal grandmother to thank for an early introduction to natural dyes. She regularly used onionshells, tea or marigolds to revive clothing that had become shabby. Throughout my childhood my mother would guide my brother and me in the annual wrapping and boiling of eggs in herbs and onionshells, to celebrate Easter but it wasn’t until many years later that the penny dropped and it occurred to me that this was a brilliant means of dyeing cloth.

I made a few experiments but really owe my career in dyeing to Henny Penny, a white Leghorn who laid her eggs in a nest made from dried eucalyptus leaves. Heavily pregnant with my third child, I lazily didn’t collect the eggs during three days of torrential rain, merely hurling grain into the fowlyard and running back to the house for cover. When I eventually retrieved the eggs, they had been printed with leaf shapes in the warm and humid atmosphere under those fluffy feathers. That was in 1991 and though I was slow to explore the discovery (I didn’t publish about the eucalyptus ecoprint until 1999, at the White Nights Textile Symposium in St Petersburg, Russia) I later recognised that this was absolutely a life-changing moment.

Can you tell us more about the leaves, roots and bark that you use for your dye, as well as the base fabrics you use and the processes involved?

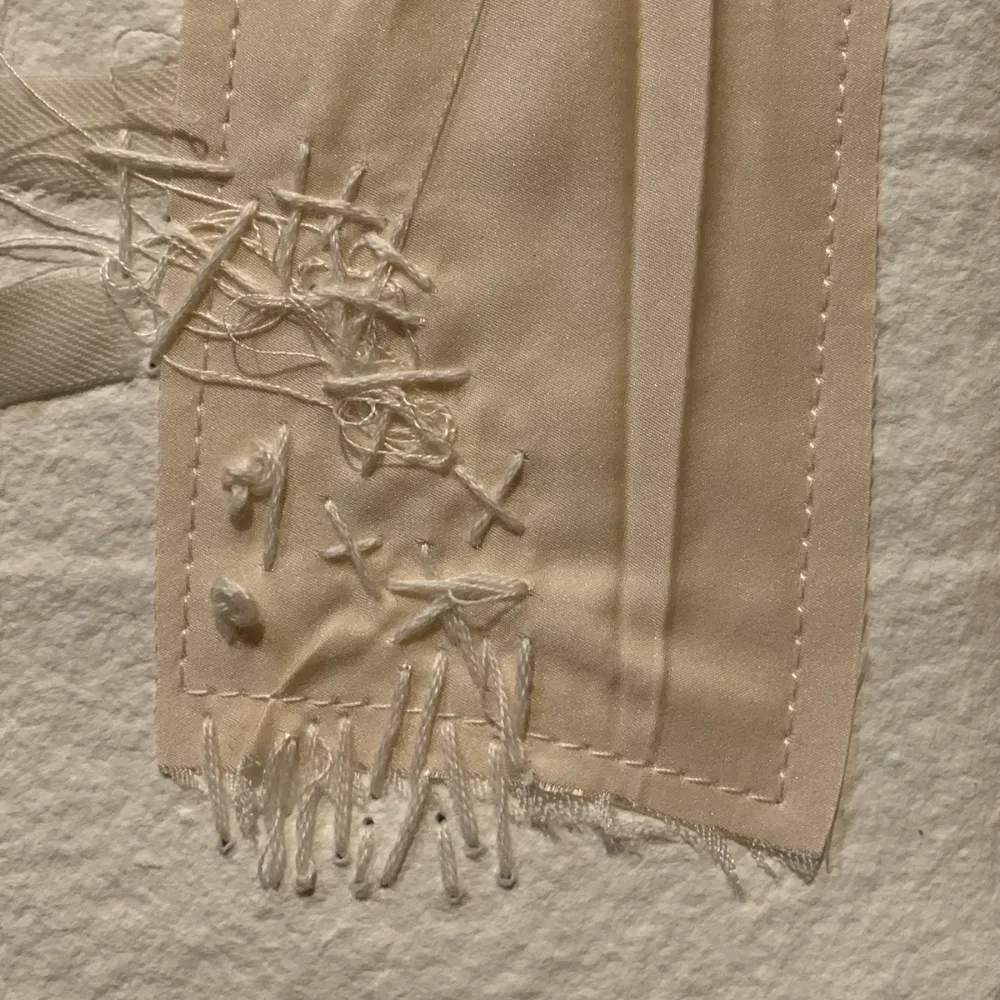

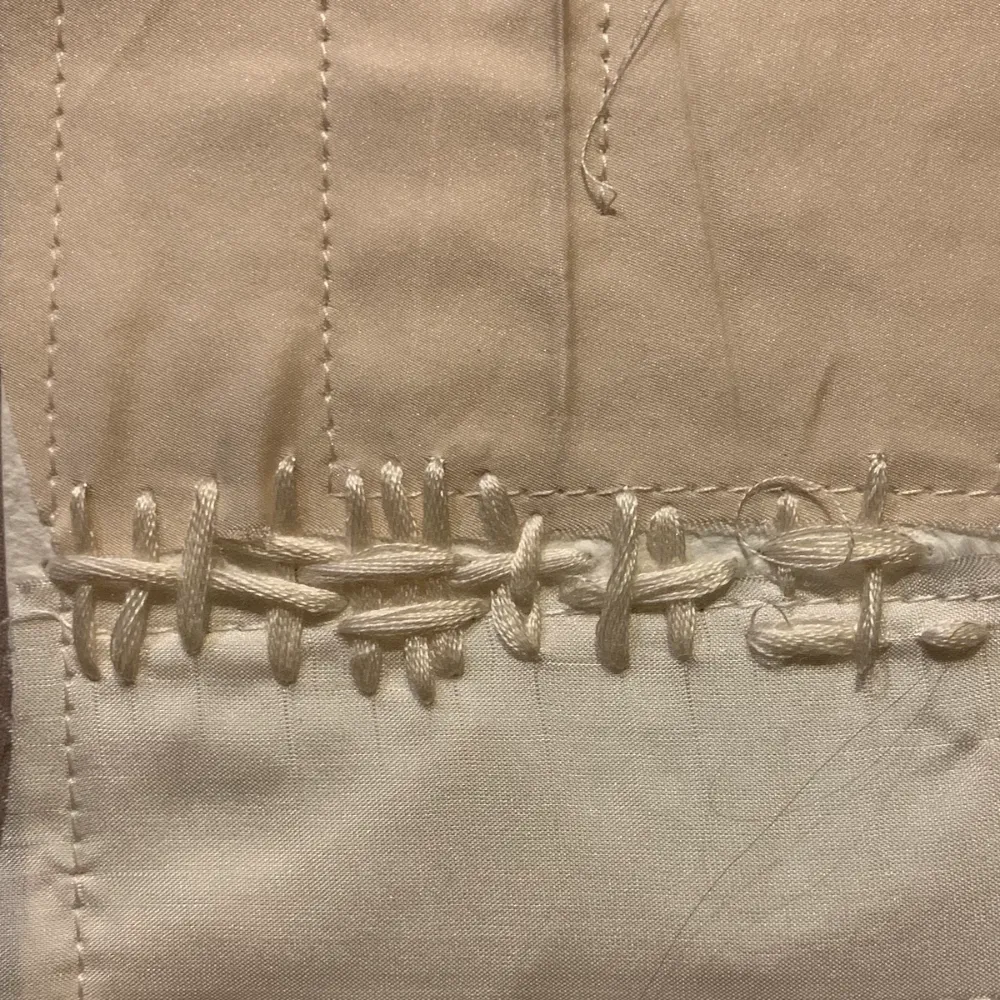

The process really is ridiculously unsophisticated, and relies on quite basic chemistry. All plant dyes in their natural state are acidic (including indigo, which is why fresh indigo has such an affinity for silk). Very simply explained (and physicists will be rolling their eyes in horror here), acidity would suggest that there is a negative charge. As I understand it, proteins are positively charged, ergo the combination of a plant dye and a protein fibre results in a molecular bond. The complications of mordants are another matter and a longer story. Rolling leaves in cloth and tying the bundle tightly means that (as the bundle is heated) the dye participles are literally forced into the cloth under pressure, resulting in a contact print. It is such a simple magic.

I prefer to work with local colour wherever I happen to be (though in recent years I have permitted myself to be seduced by indigo) and so here at home on the farm I work mostly with indigenous plants including eucalyptus, grevillea, callistemon, agonis, chamelaucium and acacia. Eucalyptus is decidedly my first love as every part of this genus will yield some kind of colour…and the range is astonishing, from green and yellow through gold, orange, tan, rust red to brown, black and even purple.

How do you feel that Australia’s dramatic colour schemes, light and rich cultural heritage are reflected in your work?

I’m not so sure I have the right to claim any Australian cultural heritage having been born here quite by chance, the child of two people displaced by that war in the middle of the last century. Most of my DNA is from Latvia and Prussia with a dash of Celt, a splash of Kazakh, a smidge of Scandinavian and a sprinkling from the former Austro-Hungarian Empire. However, I can certainly claim to have revealed the magic of the eucalyptus ecoprint by virtue of dye traditions inherited from that complex background and I do love this country, especially the parts where people are not.

Eucalyptus dyes are not a part of local traditional knowledge, but required European dye methods in order to extract their colours by boiling in water. Australia’s first people were a stone culture, rather than a metal-smelting one, and so the likelihood of being able to maintain water at boiling temperatures for the forty-five minutes necessary to create either a dye solution or a print on cloth is fairly slim. Some have suggested this could be done by adding heated rocks to a pool but I very much doubt that. Finely woven protein-based cloths were not known either, which further complicates the theory, and though leather can be printed with leaves there is no evidence of that having occurred. I have observed however, in the years since I have made the technique public, the eucalyptus ecoprint has been adopted and claimed by several First Nation practitioners working with textiles.

But sharing the practice does not diminish my joy in it, and I love that cloth printed with leaves reveals the colours of the land, even smells like it. If I wear a home-printed shawl abroad and it comes on to mizzle, or when wandering in fog, the fragrance of home awakens with the humidity, so much so that other people have remarked on it (which is why there are certain acacias that I avoid, as they smell far too nitrogenous!).

We’ve noticed that our students are increasingly interested in ecologically sound dye and print methods when completing their coursework. Do you have any advice for them when just starting off and making the move away from synthetic dyes?

Read. Learn the names of the plants that surround you and research their properties. Know what you are dealing with. Roughly 80% of plants in the average suburban garden (whatever that may be) have properties that may affect human physiology in some way. Just because things are ‘natural’ doesn’t necessarily make them safe. Avoid the use of plastic barrier layers in your bundles, use old sheeting or paper (hanji paper is fabulous) instead. Embrace the adventure, treat “failures” as a pre-mordant for the next layer, wrap each bundle as though it were a gift to yourself and use windfalls or discards wherever you can. There are too many people on the planet now, for wild foraging to be sustainable.

What’s next?

I don’t have any exhibitions planned at present. But, I am slowly working on a book, provisionally entitled provenance (with a small ‘p’) that is unfolding as a compendium of stories and images, peppered with a few recipes (both for good food and for some other things). It should have been completed by now, but it’s proving a slow wandering via fountain pen and ink that keeps leading me astray on a sideways dance along paths that often turn out to be (in the words of a certain much-loved bear) strands of marmalade dried on the map.

Books by India Flint

Learn More

Visit The School of Nomad Arts, or take a look at more of her work over on her website.

India Flint also write poetry which you can view here or follow her on Instagram.

Key takeaways:

- All plant dyes in their natural state are acidic (the opportunities are endless).

- Rolling leaves in cloth and tying the bundle tightly means that (as the bundle is heated) the dye participles are literally forced into the cloth under pressure, resulting in a contact print. It is such a simple magic.

- Working with local colour is great. What indigenous plants are in your area?

- Learn the names of the plants that surround you and research their properties. Know what you are dealing with.

- Avoid the use of plastic barrier layers in your bundles, use old sheeting or paper (hanji paper is fabulous) instead

- Embrace the adventure, treat “failures” as a pre-mordant for the next layer.

2 Comments

I have always loved gum leaves. I collected them when small and made patterns on paper. I collected beautiful 9 to 12 inch leaves from the footpath under a tree near the station on my way to work. I often had a bunch of leaves in my handbag when I got to work. I recently used these old dry leaves to dye some silk for a special project and they gave me beautiful prints. My love continues.

That sounds amazing Josephine. Thank you for sharing this.