As a highly skilled Hand Embroiderer and artist working in costume, Michele Carragher has worked on countless award-winning productions including, Elizabeth 1, The Crown (season one), and even Game of Thrones (GOT). Her early interest in textiles, subsequent training at the London School of Fashion and shear brilliance has led her into a fascinating career – a dream job for many!

We had the absolute pleasure of catching up with Michele to discuss her career to date! We asked her about her favourite pieces, how she got into costume embroidery and of course, how she approaches each project.

Costume Embroiderer sounds like a wonderful job description! Can you tell us more about what that entails exactly and what training you did to get into it?

I do consider myself very lucky to work in such a wonderful creative field. All aspects of the costume are character driven, cut, colour, style and small details – all combining to portray narrative to the viewer.

For me initially the Costume Designer will show me some illustrations and mood boards for ideas they wish me to work on. I will go away and research for the design, do some sketches, gather materials together and create some samples. I will show the sampling to the designer and then things will develop from there.

As to training for this area of work I can only really describe my own route into this career, as there are no specific costume embroidery courses to prepare you for this work.

From a young age I was encouraged to sew by my mum and grandmother. I started with creating outfits for my dolls, before attempting my own ensembles. I studied fashion design at college, where I really enjoyed the craft based modules, such as millinery and embroidery. The fashion embroidery was more machine based, but there was also a City and Guilds Hand Embroidery course where they experimented more with printing, smocking and hand embellishments so I was always looking in at their projects.

After college I had the opportunity to work in textile conservation as I had the hand embroidery skills required. It was here where I honed my hand needle skills, building up speed and precision on each piece I worked on. Much inspiration was to be had from all the textiles that passed through my hands and all the skills I learned here have proved invaluable for my work in film and TV.

I first started to explore the world of costume through a group of friends who made short art films and then had the chance to work on a low budget feature film where I was most fortunate to meet and work with Mike O’Neill the costume designer on this production. He was a very experienced designer, who usually worked on period TV dramas and after this initial job he became a great mentor to me.

I began by working with him as a general costume assistant, learning about script breakdown, character analysis, costume plots, sourcing costumes, buying fabrics and trimmings, working with makers, going to the costume hire houses, attending fittings, working on set, documenting continuity of costumes for each character, maintaining the costumes, preparing for each filming day, so getting an all round education on the costume department. Mike was aware of my sewing skills so he gave me little makes or embroideries to do on each project we worked on and I gradually migrated towards the embroidery and embellishment of the costumes. Mike then gave me my first role solely as principal costume embroiderer, which was on the HBO mini-series Elizabeth I starring Dame Helen Mirren.

I do think that starting out this way working as part of a smaller team on TV productions is a fantastic way of gaining an overall education in the costume department, as you get to do a bit of everything and see how the team work as a unit for the designer. Big budget film projects are great too, but you tend to be confined to one area so you miss out on understanding the department as a whole. I always encourage those interested in working in this field to take any opportunity that crosses their path as you never know where it may lead, I have many friends and colleagues who all started out with jobs dressing in the theatre and again this is where you meet contacts who may call on your services in the future. Also you may imagine yourself as possibly an assistant designer, but then once immersed in a production find that your skill set is best suited to other areas – so again always be open to other avenues and where they may lead.

Virtuoso waistcoat

You’ve worked on some amazing productions such as Game of Thrones, The Crown, Assassins Creed and Elizabeth 1. How did you first get into working for film and TV and how much involvement do you have with the actual cast and/or spend time on set?

Once you get a foot in the door, all work is via word of mouth, as the same teams tend to work together from project to project, and as you gain experience and meet new people they become your network for future contacts. Each project will vary in scale and what is expected of you, but generally as a costume embroiderer you don’t normally have much interaction with the cast or go on set, as you are usually too busy in the workroom consumed with creativity and juggling deadlines.

On some projects I will attend a fitting, which is really helpful for me to see how a design is working, or not, for a particular actor and gives me a much better idea of how to proceed with each piece with placement, colour palette, how the embroidery is combining with the cut, colour and overall design for the character. I am rarely on set these days, but again if possible it does help you see how the costume translates to screen, you can see the setting, how the scene is to be lit and what is happening within the scene – which can all inform the design.

Do you have a favourite genre – fantasy, historical etc? If so, why?

I don’t really have a preference as to genre, each project presents challenges – an on-going learning process, experimenting through sampling on each project helping you store up knowledge for future designs. For historical pieces, it is fun to research and try to find more unusual examples of a specific technique for your inspiration to inform the designs you will be asked to do. Even on historical dramas, you will mostly be creating an impression of the period, there may not be time or budget to recreate historically accurate pieces and the production itself may be a stylised version of history, this will all be under the direction of the production company, the show runners, the writers and the directors.

For fantasy/sci-fi you obviously start from a place of more freedom as you aren’t tied to a particular period or place in history. However you still need to ensure that everything is believable for the character, their setting, or place in the world, their status and personality. So, although it is a fantasy genre it should still be rooted in the reality for that character.

What was your first memory of stitching – who taught you?

My first memories of stitching were at school and with my grandmother. At primary school we all had to do a sampler and I also recall embroidering my name in chain stitch using purple thread for my PE kit bag. We did some knitting too, I remember everyone in the class, boys and girls having to knit a teddy bear. My grandmother was a competitive WI member and was always working on a creative project, painting, knitting, crochet or embroidery. I did help with an embroidered tablecloth she was working on and my favourite stitch to do was the French knot.

What kind of direction do you get when being commissioned to work on a production – is the brief left open for your interpretation or are you given exact requirements?

It will vary from each Costume Designer I work with, I may be asked to recreate an existing design or historical piece, so that will entail trying to source the right materials for the particular technique.

Some designers have a very clear idea of what they want, others will leave you to sample and experiment and then through the sampling process steer the design in their desired direction.

I do have a fairly free rein and most designers like to see what you come up with that they may not have thought was possible, even if it isn’t right for that design it can spark ideas for others. But all designs will evolve after fittings and meetings with the actors, directors and producers. So you need to be adaptable and be able to develop the design responding to any notes that could come from many directions. Although I am working towards the costume designer’s ideas, there will be other voices that may give input, this could be the actor to help them with their portrayal of the character, but the directors and producers sometimes get involved too. Part of the costume designer’s job is to sell their vision to everyone involved but there is much discussion and collaboration along the way.

Can you tell us more about the sort of techniques, threads and materials you generally work with? For example, how do you go about aging embroidery if working on a historical production?

Time is always tight on a filming project and I am one small part of a large team working towards the costume designer’s vision. I need to be sure the embroidery I am working on can be achieved in the time allocated before it is needed for filming. The cut and fit is of utmost importance. Actors are often cast late and I don’t get to work on the costume until the fit is correct. Also after the costume is made and embroidered it may then need to go to the breakdown department who, age and distress costumes, so I need to have that in mind too.

I had to develop techniques to get around these time constraints, so that I could achieve intricate and opulent pieces in a shorter time frame and I began drawing on materials and techniques from my conservation work and the work I had done on earlier productions. I then started to create my embroideries on a silk crepeline or illusion tulle dyed to match the costume, creating a kind of motif I could develop further when applied to the costume. For most of my embroideries I use this technique so I can get ahead with the design whilst the costume is being made and fitted. This way I don’t hold up the costume maker’s process and I can be more ambitious with my designs.

As to the aging of embroideries, as I already mentioned there is a whole department dedicated to this. I myself choose my materials and colour palette to achieve a more antique look for the finished piece so usually less breakdown is required. A lot of time is spent sourcing different threads, beads, gemstones and trimmings etc, some vintage as well as contemporary materials. I never pass by a haberdashery, bead, fabric or craft shop without having a look round wherever in the world it may be, there will always be something useful for a future project.

Can you tell us how the embroidery and costumes come together – do you complete the item fully yourself or work closely with someone who makes the ‘base clothing’ whilst you embellish it?

I’m sure that different people work in different ways, so I can only explain my approach. There will be a costume workroom with cutters and makers, so I will be liaising with them closely. The shapes will be cut first and once there have been fittings, things may need to change to suit the actor’s aesthetic and physique before I would get access to the garment for the embroidery.

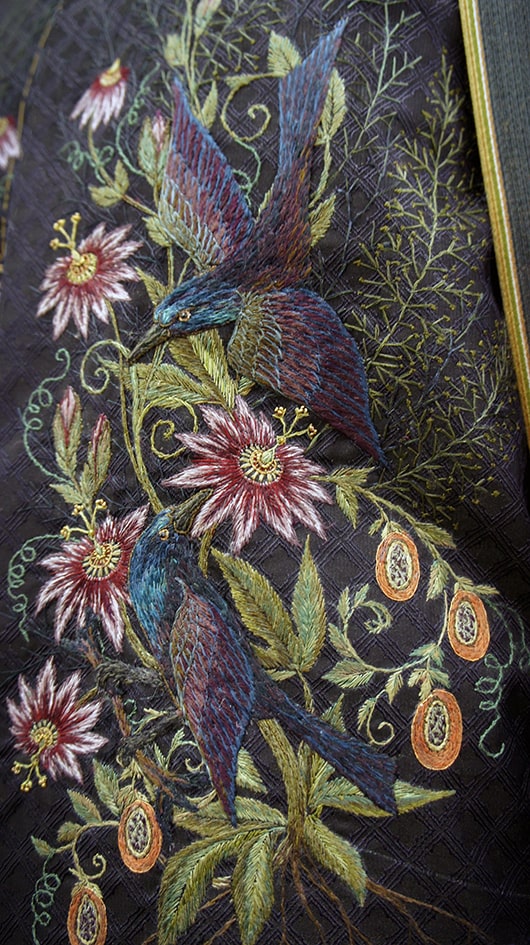

I have occasionally had flat pieces to work on with the possibility of framing up. On HBO’s TV series The Nevers, for example I worked on a waistcoat for a character called Hugo Swann which was embroidered using fine silk floss painting in a design incorporating glossy starlings, passion fruits and flowers. Another embroidered waistcoat I worked on was again for a male character this was for a pilot programme set in the 18th century called Virtuoso. I was given some vintage Peking knot work motifs as a starting point for the design, which had floral elements and two stylised peacocks as part of the final piece.

Generally, men are less difficult to fit so there is the possibility of working the embroidery on the fabric before it is cut out to be made up. Or if the fittings happen early enough to facilitate this then I may get the flat pieces to embroider, such as on a film called Queen of the Desert for which I worked on two ball gowns created for Nicole Kidman’s character portrayal of Gertrude Bell. These were inspired by the father of haute couture Charles Frederick Worth.

Gertrude Bell’s ball gown for Queen of the Desert

On another project, the 2020 adaptation of The Secret Garden there was a small team creating fabric designs that were hand printed and then I embellished those prints all of which I could do on the flat before construction and then add final touches when the garments were fully made up. But again, even with this possibility, I need to have in mind when there are to be subsequent fittings and how long the makers need to construct the garment and then maybe factor in breakdown too. So it does tend to be a juggling act between all of us and at the back of your mind you need to be aware the schedule changes, potentially meaning the costume is needed earlier than expected so you need to be adaptable.

On Game of Thrones most of the designs I worked on were realised by creating the early stages of the embroidery separate to the costume whilst it was being fitted and made. For several female characters, who resided in the land of Dorne, I was asked to create wildflower embroideries for some of the dresses they wore on more formal occasions. For these I created the early stages of the embroidery on some invisible organza dyed to match the costume and then applied the pieces to each dress, further embellishing with stitch, ribbon work and beading.

The character Daenerys, wears pieces which are more textural. These represent dragon skin to reflect her inner strength she gets from her dragons and for these I created separate smocked pieces that I stitched onto the constructed garment and then used stitching to blend the joins and assimilate the texture onto the costume. For another character, the Queen Cersei I worked on many different designs but one that I really enjoyed was her gorget and pauldrons, creating a form of jewelled armour. For these the cutter created the base shapes for which I then worked on making filigree pieces and stumpwork lion heads that I then stitched to the base shapes, adding extra trimming and glass spike beads.

It is vital to have great communication with others in the costume department to achieve the best results possible in the timeframe available.

Daenery’s Costume for the Game of Thrones

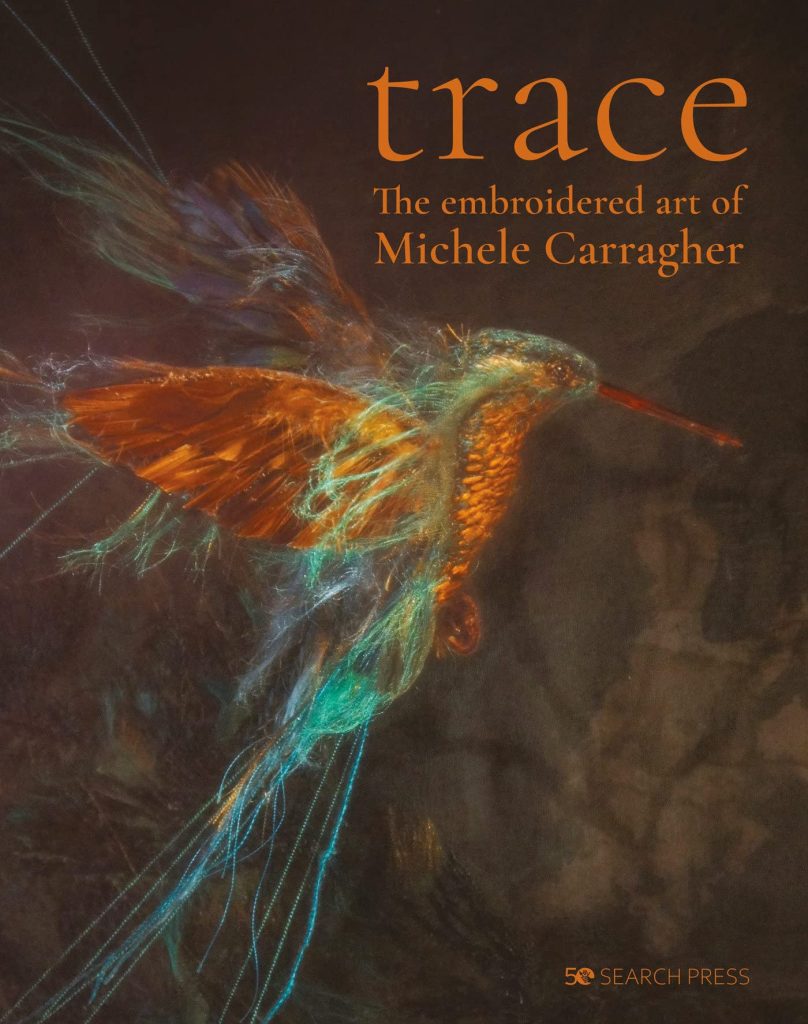

Your book, Trace, is wonderful and the photography is amazing – can you tell us a little about how you compiled it?

Because of the embroidery work and costumes for GOT being highlighted in the media, I was approached by Search Press to create a book. They commissioned me to work on a publication incorporating my own art using the embroidered medium.

Initially I spent a long time thinking about what I wanted the work to be about and how I wanted the structure of the book to be, presenting what I imagined to be a print form exhibition of my work.

I wanted to celebrate the embroidered medium and show case the possibilities it affords.

As part of my work in costume I often visit museums for inspiration and chose this as a starting point, the moment you are confronted with a piece on display and the dialogue that it initiates. Often each artefact is set in an empty space, and this is the area that my thoughts on it start to invade.

What the piece says to me initially about the design, the material, the construction, but then the narrative behind as to whom it belonged, who made it, the social climate of the time and place and how that now sits in the world we live in today. So for the inspiration for each artwork I started with an embroidered artefact, which I chose to create myself and then embroider the narrative that spoke to me about it in the surrounding space – these artefacts became my sketchbooks for the final artworks.

From the outset I had a clear vision treating the book as a whole as the artwork, from cover to cover. I wanted the first chapter to be an exhibition; a gallery tour of the artworks, each has a colour palette, a title and quotes to suggest themes woven into each piece.

The second chapter, the artist’s insight, shows the thoughts and processes involved behind the artworks that comprise Trace. I introduce each artefact, what that spoke to me, extracting a narrative to inform the subsequent artwork. I then show an insight into the different materials and techniques to achieve the various elements, firstly of the artefact and then the following artwork.

The final chapter of the book is about me, my background in textile conservation and my work in costume, culminating with some close-up details of various costumes I have worked on.

From the initial conception of the book to it finally being published took around 4 years. I did spend over a year on the concept behind the work and then embarked on creating all the artefacts and artworks. I was about half way through the making when Covid took hold on the world and so spent most of my lockdown time working on the book. Again due to restrictions in place, I also took charge of the photography for the book, which was made easier as my friend and collaborator S JG Flockhart whom I share a flat with is a filmmaker/video editor.

Luckily, we had some lighting and a rather basic digital camera to work with, so he was able to step up to the challenge of the photography. Fortunately, due to his editing skills he could also grade the photographs on the computer to get the tone and look for each piece that I was after. I think going to the publisher’s photography studio at that point in time was not an option and it wasn’t the sort of artwork I could send to them to photograph without direction from me, so ultimately, I was fortunate to be able to do this myself at home, with a lot of help from my friend of course.

When I started the project I was worried I wouldn’t have enough to fill a book. But it turned out I could have filled 3! I sent the text and photography to the editor who then started compiling the structure. I think this is where it would have been more helpful to be able to go in and discuss things as the book progressed, but with a bit of to and fro we got to a layout that was as I imagined. The final discussions were for the cover and text colour, for which I was delighted when they agreed to a foiled debossed version.

Obviously once you have completed a project you know how best to go about it the next time, should the opportunity arise, but it certainly kept me busy through lockdowns. With much help from my friend and my sister also, who had worked for many years as a fashion journalist, being involved as an editor for many publications. She was able to mock up sample covers for me to get an idea of what worked and help with lay out, structure and proof reading. Sadly my sister died before she could see the final published physical version of the book. But, I think she would have approved of what we all achieved.

Do you have a favourite actor that you have dressed and perhaps have a story you could tell us about them?

To be honest I don’t often go into the fittings to meet the actors. There is a different ‘on set’ crew team who dress the actors. Although it is really beneficial to be able to see the actors inhabit the costume breathing life into the character. Everything always looks completely different on the body as to how it does on the workroom mannequin. I worked on many costumes with a wonderful maker in Belfast, Margaret Pescott. She was the queen of inner corsetry to help sculpt the costumes to fit like a glove. One of the early characters we collaborated on for Game of Thrones was Daenerys.

I had been working on one particular dress that looked ok on the dress stand but I wasn’t sure. I got called to the fitting just so I could see how it looked on the actor and she looked amazing in it. The placement is always somewhat different on the actual body so it is really beneficial to have the opportunity to at least see photos from the fitting, if it isn’t possible to attend it yourself.

What is next? Do you have exhibitions or new books underway that you could tell us a little about?

As to what is next, I continue to work on costumes for film and TV, but also have in mind more personal art projects to achieve. Working in film and TV can be all consuming, as the working day is 10-12 hours plus possible 1-2 hours commute to a studio, which leaves little time for anything else. But in between I am determined to pursue my own work as an artist.

I am currently in the process on getting the pieces from my book Trace framed up so they are suitable for exhibition. I am also working on my next body of work that could potentially be in book form that is a more accessible way of exhibiting to a wider audience, but it would be wonderful to have a physical exhibition if I could find the right space to do so.

Find out more by visiting Michele Carragher’s website, or follow her on Instagram.

Key takeaways:

- Immerse yourself in inspiration, new techniques and styles

- Always be open to other avenues and where they may lead

- Being able to adapt and evolve a design is important when working to commission

- When working in a team, communication is vital

- Never pass a haberdashery store without going in.